HOME

TOPICS

ABOUT ME

We all learn one way or another that death is part of life. But in the first six months after Emma died, Nancy and I learned something we were not prepared for.

Al Fasoldt's reviews and commentaries, continuously available online since 1983

To our daughter, Emma, on a very important day

April 6, 1997

By Al Fasoldt

Copyright © 1997, Al Fasoldt

Copyright © 1997, The Syracuse Newspapers

This is a special and very private day for my wife and me. On this day two years ago our daughter, Emma Kathryn, died.

All deaths are sad to the living. But Emma's death mixed beauty and discovery with a tragedy only mothers and fathers can know at the moment of birth. Emma started to slip away from us as soon as she began the journey an unknowable force had prompted her to take, from womb to world, three months early.

There was nothing the doctor could do. Nancy held my hands, squeezing them as hard as she could, in a rhythm that kept pace with her contractions. She tried not to cry. I watched the digits on the electronic monitors, reading them aloud for the first hour, proud of Emma for fighting so hard. When the numbers turned to zeroes, I cried, too.

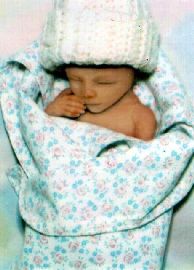

When the birthing and dying were over, a nurse wrapped Emma in a pink-and-blue blanket and handed her carefully to Nancy and then to me. We held Emma a long time. She was lovely, the tiniest little girl we had ever seen, with my dimple and Nancy's nose. She had elfin hands and a wispy smile. She weighed 17 ounces.

Someone took a picture of Emma in her blanket. She seems asleep in the picture, resting for the next journey.

We all learn one way or another that death is part of life. But in the first six months after Emma died, Nancy and I learned something we were not prepared for. We had accepted our loss and gradually learned how to deal with it, but most of those around us did not. Friends remained silent, never mentioning our baby or her death, as if she had never been born and had never died.

Others seemed surprised to hear us talk about Emma by name, as if babies should only have names if they survived past a certain point. And some even stumbled over the term we used when we referred to Emma; we called her our baby, and they used another word, "fetus," as if that would make the death more forgettable or more bearable.

We would never want to forget, and we can bear the loss. Emma will always be our child. She will always be in our hearts. It is not an unbearable pain when it is borne by love.

And we learned that grief is the beginning, not the end. We joined a support group for parents who had lost a child at birth. We found that the others in the group faced the same cocoon of silence from their family and friends, and we helped each other break that silence.

We found out how to cope.

We started by letting everyone know that we wanted to talk about our child. Nancy put Emma's picture on our refrigerator door. She put Emma's hospital handprints in a locket she always wears around her neck.

I wrote to my Internet friends and told them about our baby, and a dozen of them wrote back. Two of them told me their own stories, about their own babies, their own children who had died -- stories they had never told before.

"You have helped me open a door," one of them said.

One of them wrote a song for Emma. He sent it as a computer audio file, a minute and a half long. It has the most beautiful melody of anything we've ever heard. He called it "EmmaKate." We've posted it so you can hear Emma's tribute, too. It's a sad song -- sad because Emma never had a chance to hear it, sad because life can be full of sorrow if we let it.

But it is a rhapsody of strength and beauty, because life can be filled with joy, too. It's up to us. That is what Emma taught us, and what we will never forget.